Introduction

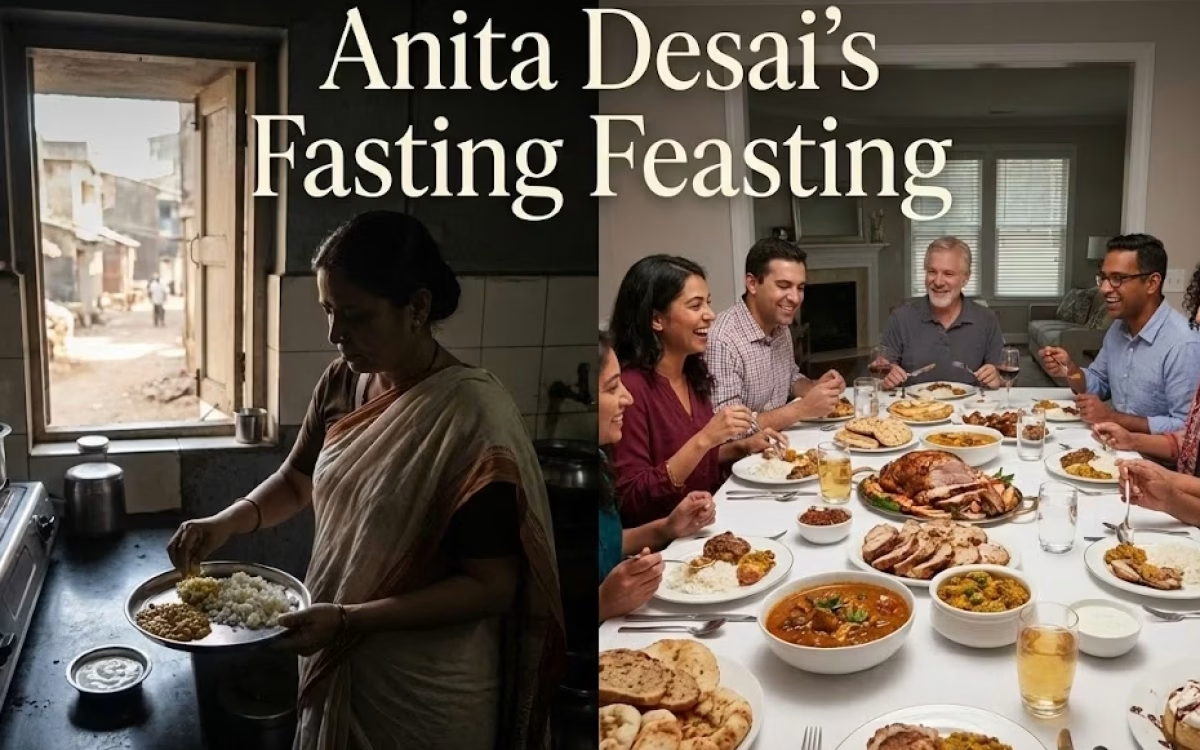

Anita Desai’s Fasting Feasting opens with the haunting contrast, “One creates a hunger where there is plenty; the other starves where there is famine.” This statement perfectly captures the emotional and psychological landscapes that define Desai’s world. Known for her deep exploration of the psychology of the outsider, Desai uses silence, repression, and longing to expose the invisible struggles within ordinary domestic spaces.

In Fasting Feasting, food becomes more than a cultural symbol—it transforms into a metaphor for emotional deprivation and control. Through parallel narratives set in India and America, Desai presents two distinct forms of consumption: one that suffocates through excess and another that isolates through neglect. The novel is not merely about appetite or nourishment; it is about how families devour individuality, consuming their children emotionally—whether through obsessive control in India or spiritual emptiness abroad.

Ultimately, Fasting Feasting compels readers to see hunger not just as physical lack but as a profound emotional condition created by systems of expectation, patriarchy, and alienation.

Quick Summary: Fasting, Feasting

Published in 1999 and shortlisted for the Booker Prize, Fasting, Feasting is a novel by Anita Desai structured in two distinct parts. Part One is set in India and focuses on Uma, a spinster daughter trapped by her overbearing parents (“MamaPapa”) and domestic duties. Part Two shifts to the United States, following her brother Arun, who is studying abroad. While Uma suffers from emotional starvation (Fasting), Arun is overwhelmed by the excess and consumerism of American culture (Feasting). The novel suggests that both systems—traditional Indian restriction and modern American excess—leave the soul empty.

Part I: India (The Fasting)

Set in a dusty provincial town in India, Anita Desai’s Fasting Feasting opens with a portrait of suffocation hidden behind domestic order. The stagnant environment reflects the emotional claustrophobia shaping Uma’s life—a world where silence weighs more than speech, and every rebellion fades quietly.

Uma, the eldest daughter, is over forty, unmarried, and awkward. Her clumsiness and naivety make her an easy target for ridicule and control. Family affection never reaches her; instead, she carries the label of a burden. In a society obsessed with conformity, her existence becomes proof of failure.

Uma’s life unfolds through a series of failed escapes—broken education, failed marriage proposals, and lost hopes of independence. Each defeat drags her deeper into submission. Even when she tries to move beyond the family home, MamaPapa pulls her back.

Desai merges Mama and Papa into a single term—MamaPapa. This unity shows how power and tradition blend to form one suffocating authority. Together, they guard a rigid order that erases Uma’s individuality. Their control feels subtle but complete, wrapped in the language of love and duty. Desai uses them to explore how women live trapped within the illusion of family affection.

The novel’s deepest tragedy appears through Cousin Anamika, the “perfect” daughter and wife. Her flawless image hides years of domestic abuse. She marries into a respectable family but faces relentless violence and humiliation. Eventually, she dies in a suspected “kitchen accident,” likely a murder disguised as fate.

Through Anamika, Desai reveals the dark truth of arranged marriage, where women are sacrificed to protect family pride. Her brutal death mirrors Uma’s slower spiritual starvation—one destroyed by fire, the other by silence.

In this first part of Fasting Feasting, India becomes a world of forced fasting, not from choice but from control. Love is rationed, voices disappear, and individuality slowly starves under the weight of tradition and respectability.

Part II: America (The Feasting)

In Anita Desai’s Fasting Feasting, the second half shifts from India’s oppressive stillness to the expansive suburbs of Massachusetts—a world defined by abundance, supermarkets, barbecues, and endless choices. Yet this apparent freedom and plenty conceal a similar emptiness. The air may be fresher, the homes larger, but the hunger—spiritual and emotional—remains the same.

Arun, the family’s long-awaited son, is ostensibly privileged. He has escaped to America, carrying his parents’ pride and expectations like invisible luggage. Free from MamaPapa’s immediate control, he is supposed to embody success. Yet Desai reveals that Arun is as trapped as Uma, confined not by tradition but by alienation. In this landscape of consumer excess, he feels lost. The smell of barbecued meat and the relentless noise of American summer disturb him; he longs for silence, for restraint. His vegetarianism becomes symbolic—a quiet rebellion against both cultures’ extremes of appetite.

Desai introduces the Patton family, with whom Arun stays during vacation. At first glance, they appear to represent the ideal of Western freedom—smiling, talkative, and open. But beneath their cheerful exterior lies fragmentation. Mrs. Patton tries to mother Arun through food, filling her freezer with meals no one eats, mistaking consumption for care. Her effort to please him turns into another form of suffocation, echoing the cloying affection of MamaPapa.

The family’s daughter, Melanie, provides one of the novel’s most striking parallels. Living in a world of plenty, she suffers from bulimia—a compulsion to gorge and purge that reflects her inner turmoil. Uma fasts because her parents deprive and control her, while Melanie starves and purges despite living in plenty. Both women live trapped in destructive cycles—one consumes denial, the other rejects disgust.

Through this American landscape of “feasting,” Desai dismantles the myth of Western fulfillment. Excess becomes another form of emptiness, consumption another form of control. By the end, it is clear that whether in India or America, hunger—physical, emotional, or spiritual—remains the universal condition of human confinement.

“Anita Desai’s prose is incredibly sensory—you can smell the frying snacks in India and the raw meat in America. To truly appreciate the contrast, you must read the original text. [Buy Fasting, Feasting on Amazon].”

Major Themes

Anita Desai’s Fasting Feasting explores universal patterns of desire, deprivation, and misunderstanding across two continents. Through the motifs of food, gender, and communication, Desai reveals how both Indian and American societies create different forms of hunger—emotional, social, and spiritual.

1. Food as Symbolism

Food is one of the most powerful symbols in Fasting Feasting, representing control, excess, and emotional starvation. In the Indian household, food is sacred but tightly rationed. MamaPapa decide who eats what and when, reinforcing hierarchy and dependence. For Uma, eating is never about pleasure; it is about obedience.

In America, food becomes the opposite—abundant, industrialized, and meaningless. Supermarkets overflow, freezers are stuffed, and meat sizzles constantly on outdoor grills. Yet this excess inspires disgust rather than satisfaction. Arun, a vegetarian, is repelled by the raw meat and the careless waste around him. Desai contrasts India’s scarcity with America’s abundance to show that both extremes—control and indulgence—lead to spiritual emptiness.

2. Gender Roles

Desai’s portrayal of gender is central to her critique of family and culture. In India, Uma is denied education and freedom simply because she is female. Her destiny is dictated by patriarchal tradition—marriage, servitude, and silence. In contrast, Arun is compelled into education and achievement because he is male, even though he finds no joy in it. Both siblings suffer under gender expectations: Uma from enforced dependence, Arun from imposed ambition.

By showing how these roles stifle individuality, Desai dismantles the illusion that gendered duty ensures happiness. Whether confined or pressured, both characters reveal the cost of living according to someone else’s script.

3. Communication Failure

At the heart of Fasting Feasting lies a profound failure of communication. In the Indian household, Uma’s voice is suppressed; her words vanish under MamaPapa’s authority. Conversations exist only to affirm hierarchy, not to share thought or emotion.

In America, the problem flips—everyone speaks, but no one truly listens. The Pattons chatter constantly, filling silences with noise, while Melanie’s cries for help vanish amid casual conversation. Desai suggests that both silence and noise can isolate, and that understanding requires empathy, not abundance of words.

“If you enjoyed this, read our analysis of Desai’s other masterpiece, [In Custody], which explores the death of language.”

Critical Analysis: Feminist and Postcolonial Perspectives

Anita Desai’s Fasting Feasting operates as both a feminist critique of patriarchal control and a postcolonial reflection on cultural dislocation. Through the characters of Uma and Arun, Desai shows how the forces of gender and empire shape and distort power, identity, and freedom.

The “Third World” Woman and Feminist Reading

From a feminist perspective, Desai challenges the stereotypical image of the “Third World woman” as passive and pitiable. Uma, at first glance, fits this image—middle-aged, unmarried, and dependent on her parents. However, Desai slowly reveals her as a woman of quiet resilience and inward richness. Her joy in collecting small treasures like Christmas cards, her devotion to saints and pilgrimages, and her fascination with faith mark her as deeply spiritual and imaginative rather than broken.

Desai’s feminist lens uncovers the subjectivity of women like Uma, whose richness of thought and subtle resistance often go unnoticed. Uma does not fight openly against her parents, but her acts of curiosity and compassion are, in themselves, forms of rebellion. By centering such interior lives, Desai exposes how patriarchal systems starve women of opportunity while underestimating their emotional and intellectual vitality.

Postcolonial Critique of the West

From a postcolonial standpoint, Fasting Feasting interrogates Western ideals of progress and freedom. Many Western readers approach the novel expecting America to represent liberation for characters like Arun—a space where he can escape the rigidity of Indian tradition. Yet Desai subverts this assumption. In the United States, Arun encounters not liberation but loneliness and disconnection. The culture of convenience and consumption leaves him feeling more alienated than before.

Desai’s portrayal of the Patton family dismantles the myth of the West as a moral or emotional refuge. Their abundance of food, speech, and freedom conceals emotional hunger and superficial relationships. In contrast, India’s oppressive togetherness suffocates individuality. Neither world provides true nourishment for the soul. Through this critique, Desai exposes how the colonial mentality continues to idealize Western life and marginalize Eastern identity.

Ultimately, the novel positions both societies as flawed mirrors—one fasting, the other feasting—each revealing the other’s moral emptiness. Desai’s feminist and postcolonial insights converge in her central truth: hunger persists wherever empathy and understanding are denied.

Conclusion

Anita Desai’s Fasting Feasting concludes with a quietly powerful gesture—a shawl sent from Arun to Uma. This simple gift, bridging continents, becomes a symbol of connection and recognition between two silenced souls. For the first time, Uma receives something that is not an order, expectation, or judgment, but an act of empathy. The shawl represents warmth, understanding, and the fragile bond that survives across physical and emotional distances.

Through this final image, Desai unites the novel’s two worlds—India and America—showing that beneath their differences lies a shared emptiness. Whether in a house of fasting or a land of feasting, humans remain bound by the same hunger for love, belonging, and understanding. The novel ends not with resolution but with quiet acceptance: true nourishment comes not from food or freedom, but from compassion and connection.

FAQS

Why are the parents called MamaPapa?

Anita Desai uses the combined name “MamaPapa” to emphasize that Uma’s parents have no individual identities. They operate as a single, inseparable unit—a united front of authority and tradition. Their merger symbolizes the oppressive constancy of the patriarchal household, where family control replaces personal emotion, and autonomy is dissolved under a shared will.

What does Melanie’s eating disorder represent?

Melanie’s bulimia reflects the deep spiritual emptiness of a materialist society. Surrounded by abundance, she literally consumes and rejects it, mirroring the emotional waste and excess of American life. Her condition parallels Uma’s forced fasting in India—both women are caught in cycles of deprivation, one amid scarcity, the other amid plenty.