Introduction

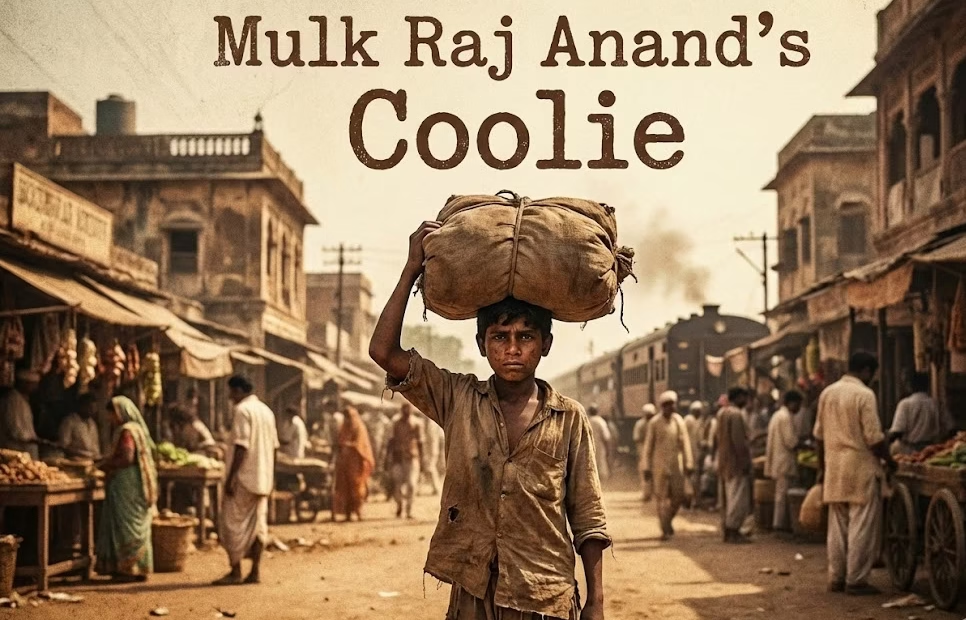

Mulk Raj Anand’s Coolie captures the tragic pulse of colonial India with a piercing honesty rarely seen in early Indian English fiction. In the West, the ‘picaresque’ hero usually survives. In Anand’s India, he dies. This reversal sets the tone for a narrative that refuses romantic escape and instead confronts the crushing realities of poverty and exploitation.

Anand, one of the “Big Three” of Indian English literature alongside R. K. Narayan and Raja Rao, was a writer deeply shaped by Marxist ideals and the Indian independence movement. His fiction reflects both social commitment and emotional realism, combining compassionate storytelling with powerful critique.

Coolie is not just the story of one poor boy, Munoo—it is an epic of the Indian underclass. Through Munoo’s struggles, Anand exposes how the capitalist “cash nexus” corrodes human relationships and reduces life itself to a matter of survival. The novel thus stands as both social document and moral outcry, portraying a world where innocence is continuously defeated by systemic injustice.

Quick Summary: Coolie

Published in 1936, Coolie is a landmark novel by Mulk Raj Anand. It tells the picaresque story of Munoo, a 14-year-old orphan from the Kangra hills. Driven by poverty, Munoo migrates to the plains, hoping to find work and identity. Instead, he faces brutal exploitation across four different settings: as a domestic servant, a factory worker, and a rickshaw puller. The novel is a critique of British colonialism and the rigid Indian caste/class system, culminating in Munoo’s tragic death from tuberculosis at the age of 15.

Plot Summary: The Four Stages of Suffering in Mulk Raj Anand’s Coolie

Anand structures Coolie as a journey across colonial India, where each location marks a new stage in Munoo’s suffering. His travels—from the hills to the city, from factory to luxury home—trace the economic, social, and moral collapse of a society built on exploitation.

1. The Hills (Bilaspur): Innocence and Exile

Munoo begins as a simple, carefree boy in the hills of Bilaspur, glowing with childish energy and dreams. His fragile happiness ends when his impoverished aunt and uncle send him away to work in the city. This forced separation becomes his initiation into a world ruled by money and inequality.

2. Sham Nagar (Domestic Slavery)

In Sham Nagar, Munoo becomes a house servant for Babu Nathoo Ram, a petty clerk obsessed with status. Here, Anand exposes the cruelty of India’s class system. Bibiji, the master’s wife, mistreats Munoo constantly, reminding him of his inferiority. The child learns that he belongs to the lowest rung of society—a discovery that scars him more deeply than physical abuse.

3. Daulatpur (Industrial Betrayal)

Escaping Sham Nagar, Munoo finds work in a pickle factory in Daulatpur, run by Prabha Dayal, a kind-hearted employer who treats him with compassion. However, Prabha’s business partner, Ganpat, is corrupt and eventually ruins the factory through greed and deceit. As the business collapses, Munoo is thrown once more into destitution, symbolising the fragility of small-scale industry in a capitalist system that rewards treachery over honesty.

4. Bombay (Capitalism and Class Conflict)

Munoo joins thousands of migrant labourers in Bombay, working at the Sir George White Cotton Mills. Here, Anand gives his most brutal depiction of industrial exploitation. Munoo faces the violence of the British foreman, Jimmie Thomas, and witnesses communal riots tearing apart Hindu and Muslim workers. The chaos of the metropolis reflects the dehumanising power of imperial capitalism—reducing human beings to mere cogs in a machine.

5. Simla (Colonial Exploitation and Death)

Munoo’s final stage is in Simla, where he becomes a rickshaw-puller for Mrs Mainwaring, an Anglo-Indian woman who treats him alternately as a pet and as a possession. The steep hills, thin air, and endless physical labour destroy his frail body. By the time he dies, still young and nameless, Munoo embodies the collective suffering of India’s poor—crushed between wealth and want, empire and servitude.

“Mulk Raj Anand’s writing is raw and powerful. To understand the roots of Indian English fiction, this text is essential. [Buy Coolie (Penguin Classics) on Amazon].”

Character Analysis of Mulk Raj Anand’s Coolie

Mulk Raj Anand’s Coolie is driven less by plot than by people—figures who embody the social forces of colonial India. Through these representative characters, Anand transforms one boy’s life into a mirror of the nation’s suffering and moral disintegration.

Munoo: The Innocent Victim of a Cruel System

Munoo, the protagonist, stands at the emotional and moral center of the novel. Born poor and powerless, he does not act upon the world—rather, the world acts upon him. His passivity reflects the helplessness of millions of colonial subjects trapped in poverty.

Yet, even amid deprivation, Munoo’s “zest for life” remains unextinguished. He laughs, dreams, and loves with the instinctive energy of youth. This unbroken spirit makes his eventual death all the more tragic—it is not only a human loss but the extinguishing of hope itself. Munoo thus becomes a universal symbol of innocence destroyed by an unjust social order.

“Munoo is often called the ‘Indian Oliver Twist.’ Read our guide on [Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations] to see the parallels.”

Babu Nathoo Ram: The Servile Middle Class

Babu Nathoo Ram embodies the Indian petty bourgeoisie—those who imitate their colonial masters while oppressing those beneath them. As a minor government clerk, he craves status and fears authority. In his home, this insecurity turns into tyranny, especially toward Munoo.

Through Nathoo Ram, Anand exposes the moral hypocrisy of a middle class that seeks Western approval yet perpetuates domestic exploitation. He represents a tragic irony: in serving the British, he dehumanises his own people.

Mrs. Mainwaring: Colonial Vanity and Moral Corruption

Mrs. Mainwaring, the Anglo-Indian socialite Munoo serves in Simla, symbolizes the moral decay of the colonial elite. She treats Munoo not as a person but as an object of amusement and service, a kind of decorative pet that flatters her ego.

Her shallow compassion and sensual indulgence reveal the emptiness of colonial “civilisation”. Under her control, Munoo’s physical exhaustion becomes fatal—his death, literally caused by overwork, exposes the ultimate cost of colonial indifference.

Ratan: The Spirit of Resistance

Ratan, the wrestler and factory worker in Bombay, offers a glimpse of strength and solidarity within Anand’s bleak vision. Unlike the submissive laborers around him, Ratan asserts agency—he protects Munoo and encourages collective resistance among workers.

He embodies the potential awakening of the Indian working class—the “fighting spirit” that challenges both class and colonial oppression. Through Ratan, Anand hints that redemption, if it comes at all, will rise from unity and courage among the oppressed.

Major Themes in Mulk Raj Anand’s Coolie

In Coolie, Mulk Raj Anand transforms Munoo’s tragic life into a powerful social allegory. The novel’s themes explore how poverty, power, and profit intersect to destroy innocence and humanity in colonial India.

1. The Cash Nexus: Money as the Measure of Man

Anand portrays a world where the “cash nexus” dictates every human relationship. Love, compassion, and kinship are replaced by the cold logic of economic exchange. Munoo’s uncle and aunt send him away not out of cruelty, but necessity—poverty forces them to treat him as labor, not family.

Throughout the novel, every bond—between master and servant, employer and employee—is defined by money. Anand’s message is stark: in modern capitalist society, human worth is measured by wealth, not virtue. This loss of empathy becomes the moral disease of the age.

2. Exploitation and the Double Burden of Oppression

Munoo’s suffering reflects a double burden—the internal oppression of India’s rigid caste and class system and the external domination of British colonial capitalism.

At home, the Indian elite like Babu Nathoo Ram exploit the poor, replicating the very hierarchy imposed by the British. In the cities and mills, the colonial economy uses the working class as disposable tools of production. Figures like Jimmie Thomas, the brutal British foreman, reveal the violence underpinning empire. Together, these twin forces crush Munoo’s body and spirit, leaving him no escape from systemic injustice.

3. Loss of Innocence: From Wonder to Disillusionment

At the beginning of Coolie, Munoo’s journey is fuelled by curiosity and dreams of a better life in the city. The urban world, however, quickly turns into a site of exploitation, chaos, and cruelty.

>Each new location strips away a layer of his innocence—from the domestic tyranny of Sham Nagar to the industrial hell of Bombay and the colonial decadence of Simla. By the novel’s end, Munoo’s death marks not only the collapse of one boy’s hope but also the symbolic death of innocence in a world consumed by greed and inequality.

Narrative Style in Mulk Raj Anand’s Coolie: The Voice of Social Realism

Mulk Raj Anand’s Coolie stands as one of the earliest and finest examples of social realism in Indian English literature. Through vivid detail, colloquial dialogue, and an unflinching portrayal of poverty, Anand gives voice to the silenced and invisible masses of colonial India. His narrative blends Western literary forms with the texture of Indian life, creating a style that is both accessible and deeply rooted in social critique.

The Picaresque Novel: The Tragic Journey of a Rogue Hero

The term “picaresque novel” refers to a narrative that follows a picaro—a roguish, lower-class hero—who travels from place to place, encountering various social worlds. Traditionally, the picaresque is satirical and episodic, using the hero’s adventures to expose societal hypocrisy.

Anand adopts this form but transforms it into a vehicle of tragedy. Munoo, the wandering orphan, becomes a tragic picaro—a victim rather than a survivor. His journey through Bilaspur, Sham Nagar, Daulatpur, Bombay, and Simla mirrors the disintegration of colonial India’s human soul. Unlike the Western picaro, who survives through cunning, Munoo’s innocence and vulnerability lead him to death. Anand’s adaptation of the picaresque thus aligns perfectly with his socialist vision: individual suffering becomes a reflection of collective oppression.

The Use of Indianisms: Translating Culture into English

A distinctive feature of Anand’s style is his deliberate use of Indianisms—direct translations of Hindi, Punjabi, and Urdu idioms into English. Phrases such as “rape-mother” or “eater of masters,” though awkward in English, carry the emotional flavor and rhythm of Indian speech.

This linguistic strategy makes the dialogue sound authentic, capturing the tone and temperament of India’s multilingual street life. It also performs a subtle act of resistance—forcing English, the colonial language, to carry the weight of Indian experience. In doing so, Anand decolonizes the English novel from within, giving it a distinctly Indian voice.

Critical Analysis of Mulk Raj Anand’s Coolie

Mulk Raj Anand’s Coolie combines emotional power with sharp social critique, making Munoo’s personal tragedy a lens for understanding systemic injustice in colonial India. Two especially useful approaches are to read the novel alongside Charles Dickens and to interpret it through a Marxist framework.

Comparing Anand with Charles Dickens

Critics often compare Coolie to Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist. Both novels show orphaned children brutalized by an unjust social order. For example, Oliver and Munoo are innocent figures. They expose the cruelty of institutions. These include workhouses and factories in Dickens. In Anand, they are households, mills, and colonial offices.

Moreover, both writers use sentiment and pathos. They build empathy effectively. Yet, their realism stays unsparing. Poverty, hunger, and exploitation remain central. They are not mere background details. However, Anand’s tone is harsher. It is also more politically explicit than Dickens’s. Dickens sometimes suggests individual benevolence helps. Or moral reform can ease suffering. But Anand disagrees. He shows Munoo’s death as proof. Charity alone fails in a world of empire and capitalism.

Thus, Munoo resembles Oliver Twist. Still, he is ultimately more tragic. Oliver gets rescued and reintegrated. Munoo, however, dies poor, overworked, and unnamed. He represents countless “coolies” who never escape exploitation.

A Marxist Reading: Class Struggle and Failed Solidarity

From a Marxist view, Coolie critiques indigenous class hierarchy. It also targets imperial capitalism. For instance, these forces intersect. They destroy working-class lives. Moreover, Munoo moves from village to city. This charts his shift. He goes from feudal dependence to industrial wage labor. Yet, he stays property, not person.

Additionally, the novel shows individual goodness fails. Prabha offers kindness. Ratan gives friendship. However, they cannot beat structural forces. These include debt, factory rules, and racist authority. In Bombay, Anand stages class solidarity briefly. Workers form the Red Flag Union. They prepare for a strike. This glimpse shows the Marxist solution. Only organized labor and class awareness can fight exploitation. Yet, communal rumors sabotage the strike. Hindu-Muslim violence then fractures unity. Munoo sees these events. Still, he never fully understands them. He stays politically naive. History sweeps him along.

Thus, his death shows double failure. Society exploits the poor. Also, the working-class movement cannot overcome divisions.

Conclusion

Mulk Raj Anand’s Coolie ends with Munoo’s death. However, the novel clarifies one key point. He does not die from fate or weakness. Instead, a corrupt system grinds him down. For example, each life phase shows this truth. First comes domestic service. Then factory labor. Finally, rickshaw pulling. Poverty, caste, and colonial capitalism combine. They exhaust his body. They also erase his identity. Moreover, Anand rejects easy rescues. He avoids sentimental endings too. Thus, Munoo’s tragedy feels structural. It is not accidental. His death proves a harsh reality. Society values humans only as cheap labor. They become replaceable. They fade quickly.

Ultimately, Coolie challenges readers. It forces us to see invisible workers. They build cities and ran households. They sustain comforts. Often, they pay with health, dignity, and life. Through Munoo, Anand demands recognition. Countless “coolies” remain unseen today.

FAQS

Why does Munoo die at the end?

Munoo’s death is not random tragedy but a deliberate narrative choice by Anand. It demonstrates the futility of the poor man’s struggle against overwhelming systemic forces like poverty, exploitation, and colonial indifference. By killing off his vibrant protagonist, Anand rejects sentimental resolutions and forces readers to confront the hopelessness faced by India’s underclass.

What does the title Coolie signify?

The title Coolie signifies the dehumanizing reduction of a human being to a generic label of labor. Munoo starts as a named individual with dreams and personality, but society strips him of identity, treating him interchangeably as servant, factory hand, or rickshaw puller. The word becomes a symbol of how capitalism and colonialism erase personal dignity, turning people into disposable tools.