Introduction

Can you love a language that is dying? This haunting question forms the emotional core of Anita Desai’s In Custody. Set in post-partition India, the novel explores a world where Hindi has become the language of authority, employment, and progress, while Urdu lingers as the fading language of art, memory, and poetry. Through the lens of one man’s dream and disappointment, Desai paints a poignant picture of cultural decay and personal disillusionment.

At the heart of the story is Deven Sharma, a timid Hindi lecturer who still worships the beauty of Urdu poetry. His life changes when he gets the chance to interview Nur Shahjehanabadi, a once-great Urdu poet now living in chaos and neglect. What begins as an intellectual pursuit soon turns into emotional servitude. The term “custody” in the title takes on layered meaning — Deven becomes not only the custodian of Nur’s poetic legacy but also of his deteriorating world. The novel thus forces readers to question whether preserving art that no longer fits the time is an act of devotion or futility.

Quick Summary: In Custody

In Custody (1984), shortlisted for the Booker Prize, is a poignant novel by Anita Desai set in small-town India (Mirpore). It tells the story of Deven Sharma, a Hindi lecturer who loves Urdu poetry. He gets the chance to interview his idol, the great Urdu poet Nur Shahjahanabad. However, instead of a wise sage, Deven finds a gluttonous, senile old man surrounded by sycophants and quarrelling wives. The novel is a tragicomedy about the decay of Urdu culture and the burden of preserving art in a commercial world.

Plot Summary (The Disillusionment)

In Anita Desai’s In Custody, the story unfolds through the eyes of Deven Sharma, a weary, underpaid Hindi lecturer in a small college in Mirpore. His life moves in predictable circles until Murad, his old college friend and the cunning editor of an Urdu magazine, offers him an irresistible opportunity — to interview the legendary Urdu poet Nur Shahjehanabadi for publication. For Deven, this invitation feels like a call to a higher purpose, a chance to preserve the fading beauty of a dying language.

Deven’s journey to Old Delhi’s Chandni Chowk is both literal and symbolic. He expects to find a “temple of art,” a sanctuary of poetic brilliance, but instead encounters Nur’s decaying house, filled with noise, chaos, and opportunistic admirers. The poet’s home, littered with pigeon droppings, biryani plates, and half-drunk followers, becomes a mirror of Urdu’s own decline. The meeting shatters Deven’s idealism — his beloved world of poetry is not divine but painfully human and broken.

Determined to salvage something meaningful, Deven decides to record Nur’s voice for posterity. However, the plan collapses into farce when he buys a cheap tape recorder he cannot operate. The sessions are filled with interruptions, quarrels, and distorted sounds — a tragic metaphor for Deven’s failure to give order to chaos. What was meant to immortalise Nur’s art ends up as a blank tape, just as empty as Deven’s dreams.

By the novel’s end, Deven is burdened with debts, disillusionment, and emotional exhaustion, yet something within him shifts. He understands that he has unwillingly become “in custody” of Nur’s decaying legacy. Despite failure and futility, Deven accepts his role as the caretaker of what remains of Urdu poetry — fragile, fragmented, but still alive through his faith.

“Anita Desai’s prose is subtle and beautiful. To appreciate the nuances of the Urdu-Hindi conflict, you need the original text.

[Buy In Custody (Random House India)].”

Character Analysis

Anita Desai’s In Custody presents a cast of deeply human, flawed characters who embody the novel’s themes of decay, idealism, and disillusionment. Through them, Desai explores the tragic intersection of art, survival, and moral compromise in post-partition India.

Deven Sharma: The Anti-Hero

Deven Sharma is the novel’s reluctant protagonist — timid, self-doubting, and perpetually trapped by circumstance. As a temporary Hindi lecturer, he is treated with little respect at work and dominated by fear in his personal life. Yet within him burns a quiet passion for Urdu poetry, the dying art form he longs to preserve. Deven’s weakness and indecision make him the quintessential “Everyman”, a symbol of those crushed under the weight of unrealized dreams. His failure is not only external but spiritual — proving how idealism can survive even when stripped of glory.

“Deven is a Prufrock-like figure—timid and afraid. Compare him to the protagonist in [The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock].”

Nur Shahjehanabad: The Fallen Idol

Once the towering figure of Urdu poetry, Nur Shahjehanabad now lives as a shadow of his former self in a decaying house in old Delhi. Gluttonous, ill, and surrounded by parasites, he embodies the decay of Mughal culture and linguistic heritage. His physical repulsiveness — the scenes of overeating, vomiting, and fatigue — contrasts sharply with his occasional flashes of poetic brilliance. Through Nur, Anita Desai captures a haunting paradox: the artist as both a vessel of beauty and a ruin of his own excesses.

The Wives: Safiya and Imtiaz Begum

Safiya, Nur’s first wife, is sharp, practical, and manipulative. She demands money and exerts control over Nur’s declining household, representing the bitterness of a decayed domestic world.

Imtiaz Begum, the younger wife, is a self-styled “poetess” who yearns for recognition in a male-dominated literary culture. Deven’s dislike of her is telling — she threatens the patriarchal order of Urdu poetry by asserting her right to artistic expression. Through Imtiaz, Desai introduces a powerful feminist commentary on gender bias and creative authority.

Murad: The Exploiter

Murad, Deven’s college friend and the editor of the Urdu magazine Awaaz, functions as the novel’s manipulator. He preys on Deven’s nostalgic devotion to Urdu, exploiting his sincerity for personal gain. Murad represents modern opportunism — the practical, ruthless world that feeds off idealists like Deven. His character reminds readers that exploitation often masquerades as friendship.

Major Themes in In Custody

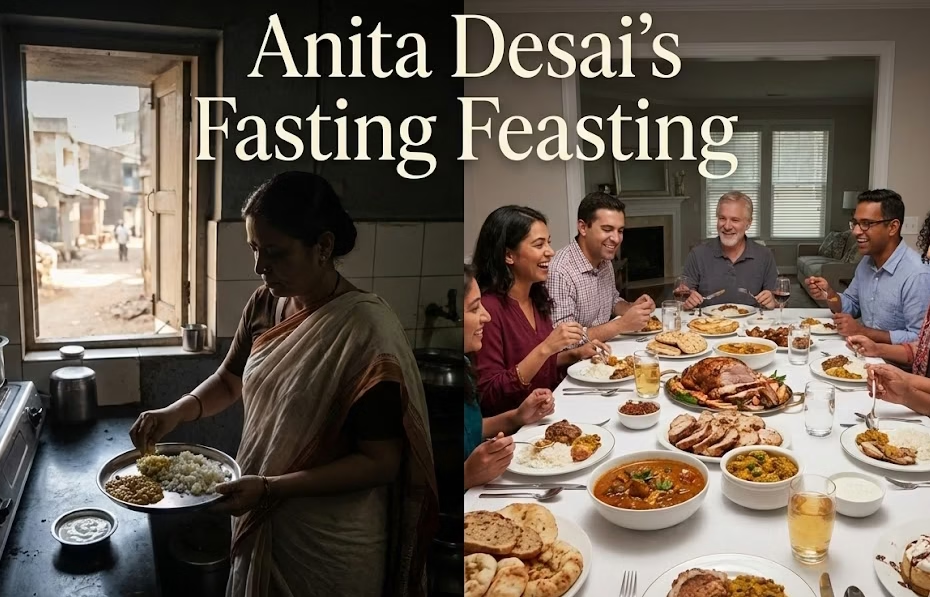

Anita Desai’s In Custody explores profound themes of language, illusion, and gender through the personal failures of its characters. The novel becomes not only a story of one man’s disillusionment but also a powerful reflection on India’s shifting cultural landscape.

1. Language Politics (Hindi vs. Urdu)

At the heart of In Custody lies the conflict between Hindi and Urdu, a tension rooted in India’s post-partition identity. Deven teaches Hindi to earn a living, yet his heart belongs to Urdu, the language of poetry, tradition, and emotional truth. This linguistic divide is more than academic — it reflects a deep cultural hierarchy. Hindi, now tied to bureaucracy and employment, represents practicality and modernity. Urdu, on the other hand, is dismissed as a “useless” luxury, romantic but irrelevant in a pragmatic society. Through Deven’s inner struggle, Desai portrays the tragedy of a language — and a heritage — fading into silence.

2. Illusion vs. Reality

Deven’s journey from admiration to despair reveals the painful gap between artistic idealism and lived reality. He worships Nur Shahjehanabad as a divine poet, expecting purity and inspiration. Instead, he encounters a decaying man surrounded by greed, noise, and filth—a symbol of how art, when trapped in human frailty, loses its glow. The “temple of art” Deven imagines turns out to be a crumbling ruin, filled with pigeon droppings and petty quarrels. Through this disillusionment, Desai asserts that art is not sacred because it is pure, but because it continues to exist amid decay.

3. The Female Voice

The character of Imtiaz Begum introduces a striking feminist dimension. A dancer-turned-poet and Nur’s younger wife, Imtiaz expresses her artistic ambitions in a space that refuses to take women seriously. Deven dismisses her work not on artistic grounds but because she is a “dancing girl” — revealing the deep misogyny in the male-dominated Urdu literary world. Anita Desai uses Imtiaz’s struggle to critique gender bias, exposing how women’s creativity is constantly diminished or mocked. Imtiaz’s defiance, however, ensures that the female voice in In Custody survives as both protest and persistence.

Symbolism in In Custody

Anita Desai’s In Custody weaves rich layers of symbolism to deepen its exploration of decay, disillusionment, and cultural loss. Everyday objects in the novel become metaphors for the larger collapse of artistic ideals in modern India.

The Tape Recorder

The tape recorder stands as one of the most powerful symbols in the novel. It represents modern technology’s inability to preserve the spirit of the past. Deven buys the recorder with the dream of immortalising Nur’s voice — to capture the essence of Urdu poetry before it disappears forever. Yet, what he ends up with is a blank, distorted tape. The machine fails him just as his own courage and competence do. This failure mirrors the broader idea that modern tools cannot contain the soul of dying art forms. The tape recorder becomes a tragic emblem of ambition defeated by reality — an artefact of both progress and loss.

The Pigeons

The pigeons in Old Delhi serve as another vivid symbol. They fill Nur’s courtyard and the crumbling rooftops of Chandni Chowk, embodying the contradictions of the old world. On one hand, these birds represent the flock of parasitic admirers who crowd around Nur, feeding off his reputation while contributing nothing. On the other hand, pigeons also stand for freedom and endurance—the lingering life of Old Delhi’s spirit amid decay. Even as the human world collapses under greed and disillusionment, the pigeons continue to fly freely above, suggesting that art and memory, though fractured, still find a way to live on.

Critical Analysis (Adaptation)

Anita Desai’s In Custody gained renewed recognition through its 1993 film adaptation directed by Ismail Merchant and produced by the famous Merchant–Ivory banner. The film, starring Om Puri as Deven Sharma and Shashi Kapoor as Nur Shahjehanabad, is a classic example of Indian-English cinema’s deep connection with literature and culture.

Moreover, the adaptation beautifully captures Desai’s balance between humor and melancholy. It transforms her introspective novel into a visually rich reflection on loss, idealism, and artistic decay. Om Puri’s portrayal of Deven highlights the vulnerability of a man defeated by bureaucracy and self-doubt. Meanwhile, Shashi Kapoor’s Nur radiates tragic majesty — the image of a poet imprisoned within the ruins of his greatness.

Cinematically, the film also preserves the novel’s symbolic depth. The decaying lanes of Old Delhi, the pigeons, and the failed tape recorder are all presented with the Merchant–Ivory trademark elegance. Therefore, the adaptation stands as a sensitive and faithful tribute, turning Desai’s meditation on cultural decline into a timeless visual elegy for lost art and forgotten voices.

Conclusion

The ending of Anita Desai’s In Custody is neither triumphant nor traditionally happy — instead, it offers a quiet, mature resolution. Deven Sharma, once naive and idealistic, finally confronts the truth of his world. He learns that art, like life, is inseparable from disorder, disillusionment, and decay. In accepting this, Deven grows up.

By the final pages, he no longer seeks purity in poetry or perfection in people. His experience with Nur and the failed recordings teaches him an important lesson. Being “in custody” means accepting responsibility for the broken remnants of culture and flawed beauty. It also means acknowledging one’s own limitations with honesty and grace. Furthermore, Desai leaves her protagonist burdened yet enlightened. In the end, she suggests that maturity begins when a person stops running from reality and learns to live within its imperfections.

FAQS

What is the significance of the title In Custody?

The title “In Custody” holds multiple layers of meaning. On the surface, it refers to Deven’s attempt to take Nur’s poetry “in custody” through the interview and recordings. Symbolically, it represents the burdens of preservation — Deven becomes the custodian of a dying language, a decaying poet, and a fading culture. The title also hints at emotional imprisonment: both Deven and Nur are trapped by their failures, responsibilities, and illusions.

How does Anita Desai portray the city of Delhi?

In In Custody, Delhi is both setting and symbol. Desai contrasts Old Delhi, with its crumbling mansions and fading grandeur, against the sterile modernity of New Delhi and Mirpore. The city mirrors the divide between past and present — Urdu’s poetic world versus Hindi’s bureaucratic dominance.