Introduction

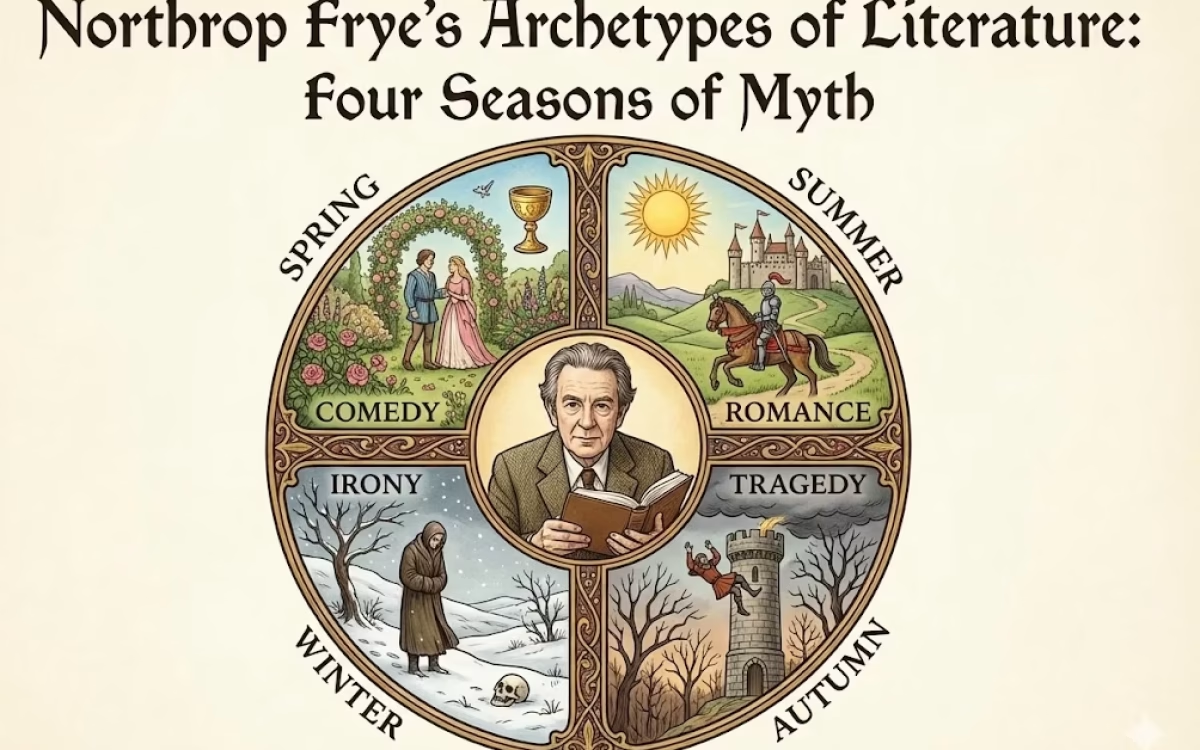

Northrop Frye’s Archetypes of Literature: Imagine if every book ever written was just a different version of the same story—myths, novels, and poems recycling timeless patterns. Enter Northrop Frye, the “Linnaeus of Literature,” who classified these patterns like a botanist organises plants in his 1957 masterpiece, Anatomy of Criticism. Frye shifts criticism from the narrow question “Is this book good?” to a bolder one: “How does it fit into literature’s larger archetypes?” This framework uncovers the seasons of story—spring’s comedy, winter’s irony—uniting all genres in a grand, mythic cycle.

Quick Summary

In his seminal essay “The Archetypes of Literature” (1951) and book Anatomy of Criticism (1957), Canadian critic Northrop Frye argued that literature is not a random collection of texts, but a unified system. He believed all literature stems from one central myth: The Quest. Frye categorized all stories into four “Mythoi” (narrative patterns) based on the four seasons of nature: Comedy (Spring), Romance (Summer), Tragedy (Autumn), and Satire/Irony (Winter).

What is an Archetype? (Frye vs. Jung)

Jung’s View

Carl Jung introduced archetypes as primordial images buried in the collective unconscious—a shared human reservoir of instincts and memories. They “bubble up” in dreams, myths, religions, and art, acting as universal blueprints that shape the psyche. For Jung, the hero, shadow, or anima aren’t invented; they reflect deep psychological drives, explaining why similar motifs appear worldwide, from Native American tricksters to Greek gods.

Frye’s View

Northrop Frye boldly flips Jung’s script: archetypes emerge purely from literature itself, forming a “total order of words” independent of psychology. In Anatomy of Criticism, Frye argues authors don’t copy life or the unconscious—they imitate prior books and conventions. Frye archetypes build through recurrence in texts, creating a self-sustaining literary universe. As Frye puts it, “The critic should… see the structural principles” in this word-based order, not chase psychic origins.

Key Differences

| Aspect | Jung’s Archetypes | Frye’s Archetypes |

|---|---|---|

| Source | Collective unconscious (psyche) | Literature’s conventions (words) |

| Origin | Innate, biological instincts | Imitation of other books |

| Focus | Individual dreams/psychology | Total literary patterns |

| Example Use | Explains personal myths | Maps genres like romance or irony |

The Definition

Ultimately, Frye defines an archetype as any symbol, character, image, or plot pattern that recurs often enough to become recognisable across literature—like the scapegoat hero sacrificed for society’s renewal (think Jesus or Oedipus) or biblical floods signalling cosmic reset (Noah, Gilgamesh). Frye spots these in literature’s mythic backbone, forming a “central narrative” that transcends authors and eras.

“Frye’s writing is dense but brilliant. For the full ‘Anatomy’, get the definitive edition: [Anatomy of Criticism by Northrop Frye on Amazon].”

The Central Myth (The Quest): Northrop Frye’s Archetypes of Literature

Northrop Frye pinpoints literature’s “One Story”—the central myth—as the quest: a hero’s journey of lost identity, trials, and triumphant return. This Frye central myth drives all narratives, from ancient epics to postmodern tales.

The Cyclical Structure

Frye models it as an endless cycle, mirroring nature’s rhythms: the sun’s rise and set, or the seasons’ wheel. It unfolds in four phases, like a year:

Spring (Comedy): Awakening and romance; identity stirs (e.g., lovers unite).

Summer (Romance/Adventure): The Hero quests outward and battles foes (think knights or Odysseus).

Autumn (Tragedy): Peak and fall; identity fragments amid hubris.

Winter (Irony/Satire): Despair and isolation, yet hints of renewal.

This loop ensures stories renew eternally—no true end, just rebirth.

Literary Power

Frye’s quest archetype powers classics like Homer’s Odyssey (wanderer reclaims home) and moderns like Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings (Frodo’s burden and return). Even postcolonial works, such as Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, echo it through cultural loss and fragile recovery. Frye unites genres here: tragedy becomes irony, comedy spirals to quest.

Spring (Renewal) → Summer (Quest) → Autumn (Tragedy) → Winter (Irony)

↑ ↓

←←←←←←←←←←←← Eternal Literary Cycle →→→→→→→→→→→→→→

The Four Mythoi: Northrop Frye’s Archetypes of Literature

At Anatomy of Criticism‘s core, Northrop Frye’s four mythoi cycle like seasons, displacing the quest’s loss-regain rhythm across genres. This framework—the narrative categories of symbols—reveals literature’s backbone, inviting postcolonial and feminist rereads.

Spring: Comedy (Birth & New Order)

↗

Winter: Irony ──────→ Summer: Romance (Zenith & Triumph)

↘ │

Autumn: Tragedy ────┘ (Fall & Isolation)

└────────────── Eternal Renewal ───────────────┘

1. Spring = Comedy (Mythos of Birth/Renewal)

Frye celebrates spring’s “myth of birth”: fertility revives, obstacles crumble. A youthful duo battles a senex blocker (proud elder or rival), forging communal harmony. Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream weaves fairy mischief into marital bliss; feminist lenses spotlight empowered Puck-like agents subverting patriarchy.

2. Summer = Romance (Mythos of Zenith/Adventure)

Summer blazes with idealised triumph: heroes quest, vanquish monsters, rescue purity in a magical realm. “The dragon-slaying romance,” Frye notes, powers Arthurian sagas or Rowling’s Harry Potter—where orphan-prophet slays Voldemort. Postcolonial reads recast quests as imperial adventures, critiquing “golden world” colonialism.

3. Autumn = Tragedy (Mythos of Fall/Decline)

Autumn’s “dying god” isolates: hubristic heroes falter via flaw or fate, toppling summer’s Eden. Hamlet broods in Denmark’s rot; Sophocles’ Oedipus blinds to truth. Frye ties this to sacrificial isolation—feminist critiques unpack gendered falls, like tragic heroines in Ibsen.

4. Winter = Irony/Satire (Mythos of Death/Chaos)

Winter mocks heroism in a demythicised hell: anti-heroes grovel amid “low mimetic” squalor. Orwell’s 1984 Big Brother crushes spirit; Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels deflates humanity. Frye’s irony mode exposes life’s absurd underbelly, fuelling dystopian satire with postcolonial irony in Achebe’s fragmented worlds.

These mythoi interlock, cycling stories from renewal to despair and back—Frye’s genius for all critics.

“Unlike Carl Jung, who believed archetypes came from our dreams and biology, Frye believed they came from other books. If you want to compare Frye’s structuralism with Jung’s psychoanalysis, read our overview of the [Psychological Approach to Criticism].”

The Cycle Continues: Eternal Literary Loop

Frye’s genius shines in the mythoi’s close: winter’s satire doesn’t freeze forever. Even in irony’s bleakest chill—think 1984‘s despair—hints of spring’s comedy flicker, promising revival.

Satiric worlds expose flaws so harshly they demand a new order. Mocked anti-heroes yield to budding fertility; chaos births structure. Thus, the Frye cycle rotates: winter thaws to spring, comedy quests into summer, tragedy darkens to irony, and back again.

Literature never ends—it loops eternally, mirroring life’s seasons. Every novel renews the “One Story.”

Winter (Irony) → Hints of Spring → Comedy → … → Eternal Frye Cycle

Conclusion

Northrop Frye transforms reading: master his “seasons,” and you forecast any plot twist—from Hollywood blockbusters like Avengers: Endgame (romance zenith) to novels like Morrison’s Beloved (ironic winter thawing to renewal).

In today’s fragmented media, Frye’s mythoi organise chaos. Libraries classify by genre cycles; streaming algorithms predict hits via quest arcs. Postcolonial critics adapt it—Okonkwo’s fall in Things Fall Apart as autumn tragedy under empire. Feminists reclaim green worlds, subverting blockers. His framework endures, blending theory with practice for bloggers, teachers, and creators.

Frye doesn’t rank “good” books—he maps their mythic dance.

FAQS

What is the difference between Jungian and Frye’s archetypes?

Jung roots archetypes in the psyche’s collective unconscious, surfacing in dreams and therapy. Frye grounds them in literature’s self-referential “total order of words”—texts imitate texts, not subconscious drives.

Why is Tragedy associated with Autumn?

Autumn symbolises fruition’s fade: ripe heroes peak then plummet via hamartia or fate, isolating like falling leaves. Frye links it to “dying gods” in works like Hamlet or Oedipus Rex.